Asia Correspondent:  17 July 2017

17 July 2017

SET to enter the fifth round of human rights talks with Laos on Tuesday, civil society groups have called upon the Australian government to criticise a lack of progress regarding basic rights and freedoms in the one-party Southeast Asian nation.

The Australia-Laos Human Rights Dialogue is set to be held in the Laotian capital of Vientiane on July 18 and 19, and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) reports to have received numerous submissions from local civil society organisations.

Australia is one of only two countries which have regular bilateral dialogue on human rights issues with the tiny communist state of Laos. Coincidentally, this year the two countries mark 65 years of diplomatic relations. The most recent Dialogue was held in Canberra in 2015.

A statement from the Australian embassy in Vientiane earlier this year highlighted “Laos’ relationship with Australia is the country’s longest unbroken diplomatic relationship at ambassador level.” Australia is also home to a sizeable Laotian community, many of whom came as refugees.

Australia is also gunning for a first-time seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council, despite ongoing criticisms of its own human rights record regarding the treatment of its indigenous population, refugees and asylum seekers.

‘Dire in just about every respect’

Laos remains controlled by the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, which tightly monitors and controls all media including TV, radio and print publications. A vaguely-worded cybercrime law from 2015 leaves citizens open to “re-education and disciplinary measures” by the regime.

Asean as a regional bloc has “largely failed to effectively address developments in Laos, which have threatened not only the enjoyment of human rights, but also the sustainability of economic development in the country,” read an official submission to the Dialogue from Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR).

“The Lao government’s suppression of political dissent and lack of accountability for abuses stand out in a human rights record that is dire in just about every respect,” Australia director at Human Rights Watch (HRW) Elaine Pearson said ahead of the Dialogue this week.

HRW’s submission to the Dialogue calls upon Australia to pressure Laos to stop conducting arbitrary arrests and incarcerating Christians and drug users. It also raises serious concerns regarding crackdowns on social media use, strict controls on academic freedom and non-profit associations.

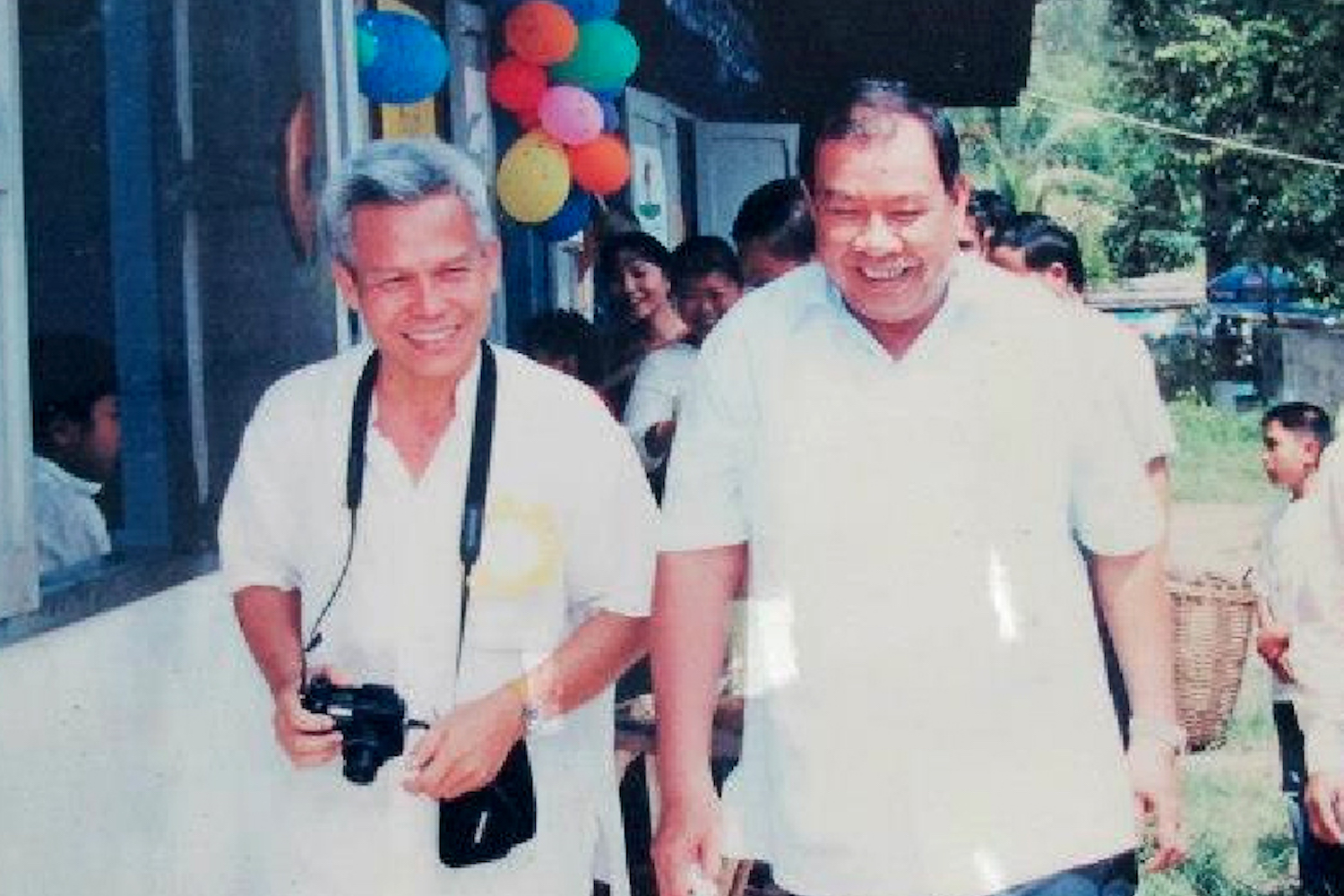

APHR sent a fact-finding delegation to Laos in September 2014 to investigate the disappearance of prominent civil society leader Sombath Somphone. The group says they were unable to meet with local organisations due to fears of government retaliation for cooperating with foreign actors.

“The disappearance of such a prominent and respected member of the Asean community was a blow to civil society across the region and the failure to quickly investigate the case damaged the Lao government’s credibility,” said Walden Bello, an APHR Board Member from the Philippines, in a statement.

APHR chairman Charles Santiago said “the human rights situation in Laos continues to be abysmal. Since Sombath’s disappearance, the space for independent civil society in the country – already one of the most repressive in the region – has narrowed considerably.”

“Meanwhile, the public remains deeply fearful of raising sensitive issues.”

Last month, the UN Human Rights Office for Asia (OHCHR) expressed “alarm” at the “very harsh punishment” of three activists sentenced to decades in prison for treason, propaganda against the state, and being involved in “gatherings aimed at causing social disorder.”

Australia’s influence in Laos

The fifth Australia-Laos Human Rights Dialogue will reportedly focus on minority rights, freedom of religion and the death penalty – a major human rights focus for Australia in the region.

One of the largest sources of foreign aid to Laos, Australia will also emphasise the right to education in a country where one in five people cannot read.

According to DFAT, Australia provided an estimated AUD44.2 million (US$34.5 million) in official development assistance to Laos during 2016-17. Australian mining companies also invest heavily in the impoverished nation of less than seven million people.

“As a major development partner of Laos, Australia can and should press for greater respect for basic rights,” Pearson said.

DFAT delegation to the Dialogue this week will consist of diplomats, Australian MPs and representatives of the Australian Human Rights Commission.

“The Australian government has a chance with this Dialogue to push for change … including an end to arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance and draconian restrictions on basic rights,” Santiago said.

“We have still not given up hope Sombath’s case will be resolved, but for that to happen, the international community – including Australia – must continue to press the Lao government for answers.”

“Australia should issue a public statement after the Dialogue to show the people of Laos the country’s human rights situation is a global concern,” Pearson said.

“These dialogues are an opportunity to raise human rights issues frankly and forcefully, but should not be the only forum to discuss abuses.”

The Australian embassy in Vientiane did not respond to request for comment.