Worldcrunch: (15 November 2013)

Police are monitoring traffic from a small wooden gatehouse in eastern Vientiane, on the outskirts of the Laotian capital. It was here nearly one year ago, opposite the Indian embassy, that 62-year-old Sombath Somphone mysteriously disappeared. The rural development promoter and farmers’ rights activist hasn’t been heard from since.

On Dec. 15, 2012, Somphone was driving behind his wife’s car in his Jeep. He was stopped by a traffic officer for an identity check. The policeman spoke with him through the car door. Somphone then stepped out and walked towards the gatehouse. Soon after, a man got off his motorcycle and climbed into Somphone’s Jeep and drove off.

A white pickup then parked on the side of the road, warning lights flashing, before two men — one of whom was Somphone — climbed in. That was the last sign of the popular activist.

CCTV footage — available on the website Sombath.org — has allowed his family to reconstruct the scenario. Since Somphone vanished, the police investigation that Laotian authorities claim to have conducted has been fruitless. What is clear is that his disappearance has all the markings of an abduction committed right before police eyes at rush hour.

“I have no idea who could be behind his abduction, or why it happened,” says Somphone’s Singaporian wife Ng Shui Meng by phone. “All I can say is that the police say that they don’t know who kidnapped him.”

The official version, repeated over and over again by the authorities and state media — the only authorized news agencies authorized in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic — is that Somphone may have been the victim of a “settling of personal accounts.” Deputy head of the police, Phengsavanh Thipphavongxay, has said that nothing proves Somphone was actually the one seen in the CCTV footage, but the missing man’s relatives have no doubt.

Theories abound

Many of his friends and NGO members within Vientiane’s foreign community think Somphone may have been abducted by a “parallel police” force or elements that are more or less controlled by a regime whose ideas with regards to development are starkly different from Somphone’s.

“Sombath claimed that the Laotian people weren’t ready for the brutal arrival of globalization,” one of his friends explains. But no one can provide evidence that the government was involved in his abduction. And his disappearance, which is still discussed endlessly within the NGO community, has allowed a climate of mistrust and fear to take hold in Vientiane.

“If one of the reasons he was abducted was to send a message to NGOs so they don’t cross any red line on issues that involve politics, then the operation has been a success,” one NGPO member says.

Everyone we spoke to for this story requested that their name and organization remain anonymous, which illustrates the atmosphere in Vientiane almost a year after Somphone’s disappearance.

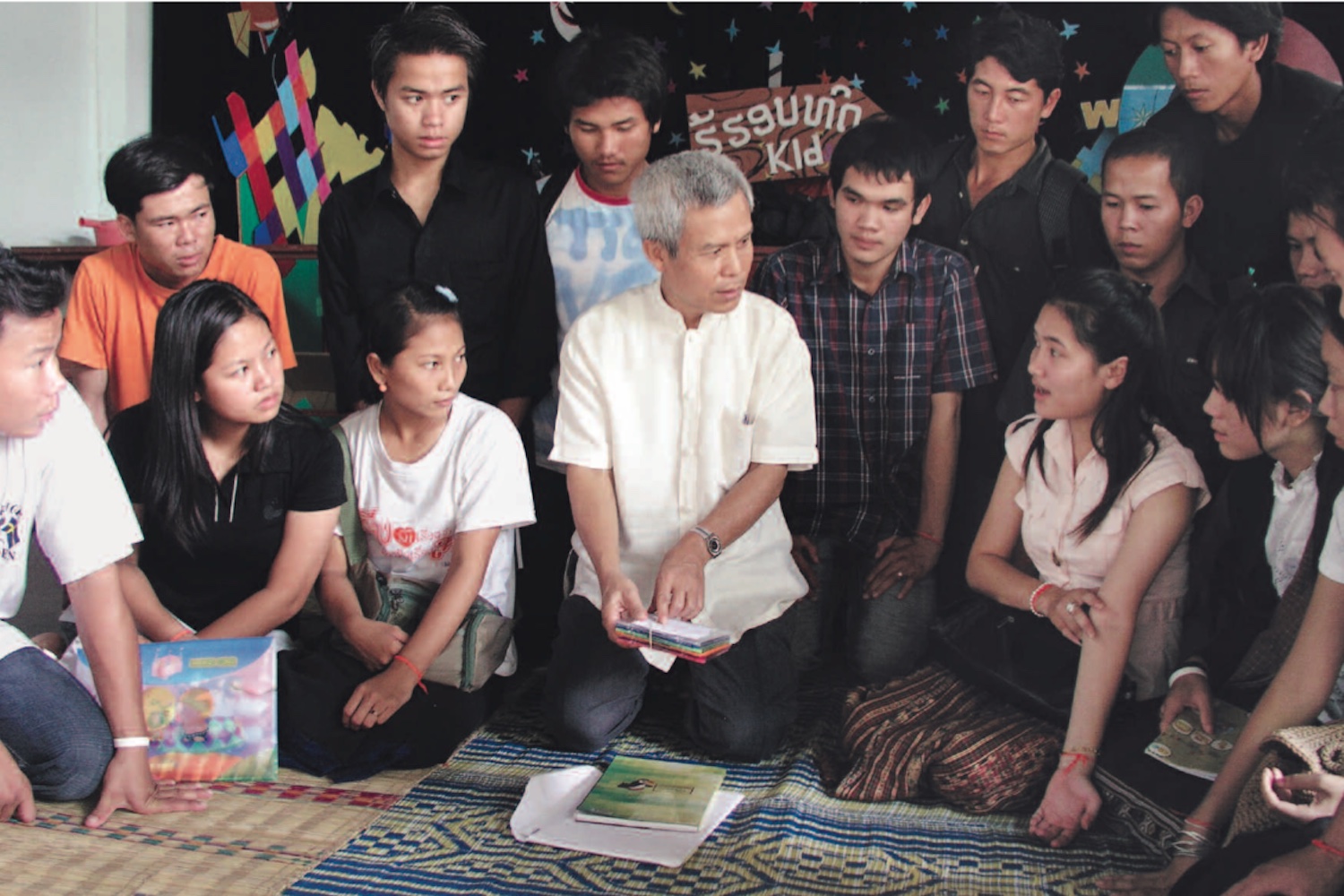

The affair caused a stir. Somphone was not necessarily well-known across the whole country, beyond the reputation he built through his Participatory Development Training Center (PADETC) that helps farmers with training and education. But he was a well-recognized figure on an international level. In 2005, this former University of Hawaii agronomy and education student received the Ramon Magsaysay Award — the Asian equivalent of the Nobel Prize — for his work in rural areas.

The world has noticed

His abduction prompted international reaction, including a direct intervention from the U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. “The U.S. share the serious concerns of the international community on Mr. Sombath Somphone’s situation,” he said March 24. “We ask the Laotian government to do all it can to provide a full account of Sombath Somphone’s disappearance without further delay.”

And on Oct. 28, while visiting Vientiane, the president of a European Parliament delegation for Southeast Asia, Werner Langen, was critical of Laotian authorities for not providing “any satisfying answers” to questions about Somphone’s disappearance.

“It seems hard to believe that the decision leading to his abduction was taken at a high level, given the amateur way those who took him away acted,” a diplomat said.

The kidnappers perhaps did not anticipate that Sombath Somphone’s family would signal his disappearance to the police the next day, and that they would then, without hesitating, show the CCTV footage to his sister and his wife. Since then, the blurry footage, which his family recorded on a cellphone, has been carefully guarded by police, who refuse to release the original video. “The Laotian authorities have refused every foreign offer of technical assistance to decipher the footage,” the same diplomat says.

Certain contextual elements could explain the efforts to silence Somphone. In early November 2012, the Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM) in Vientiane gathered European and Asian representatives. Traditionally, the ASEM is preceded by an Asia-Europe People’s Forum, which gathers NGOs and international civil societies’ spokespeople. As co-president of the organizing committee, Somphone directed the preparation of a report, “The Lao People’s Vision,” a summary of interviews with people in rural communities. During the forum, some farmers had complained about the increasing land confiscations for the benefit of Vietnamese and Chinese companies cultivating rubber trees or mining.

In his report, Somphone noted that “the expectations of a major part of the Laotian people” had not been met, “especially in terms of improving their well-being and the living conditions of the rural Laotians, who represent the majority of the population.” It was a judgment that, though not a direct attack against the regime, may have upset certain figures in power.

Ng Shui Meng cannot believe that her husband’s disappearance may be linked to this remark. She also rejects the fact that he was an “activist” or a “militant.” “He often worked in good cooperation with people from the government,” she says. “Some of them even sent me expressions of their sympathy.”

The dark underbelly of Laos

Somphone’s abduction could illustrate, for some, the evolution of a regime where the emergence of managers linked to the party are combined with operating permits granted thanks to the sponsorship of wealthy families that resulted from former “revolutionary” circles — a Chinese-like evolution that combines strict political control, market economy … and corruption.

This evolution has had a fair amount of success: a growth rate of 8.3% in 2012, a GDP per capita and per year of $1,200 (it was $300 only 10 years ago). Laos has left the category of poor countries to be among the “medium- to low-income” countries. But who benefits from this development? “Growth, growth! Government people only know that word,” a foreigner living in Vientiane says angrily. “But what does that mean when disparities are getting bigger between those who got wealthy with the system, and farmers?”

“On the surface, Laos is a radiant and happy country, a haven for tourists in need of tropical exoticism,” one Laotian intellectual from Vientiane says. “But underneath, it’s very different, a place where it’s getting much harder to live.”