Reuters Alternet: 16 September 2013

By Anne-Sophe Grindroz

In December 2012, Sombath Somphone was following his wife home for dinner in Vientiane, the capital of Laos, driving in a separate car. On Thadeua Road, he was pulled over by traffic police. That was the last time his wife or anyone else saw him.

While numerous foreign governments, global leaders, parliamentarians and civil society organisations have inquired about Sombath’s whereabouts—to no avail—the land rights of Laos’s rural poor and indigenous communities that Sombath championed remain under the radar.

Large multinational corporations are swooping into Laos and other “underdeveloped” countries to acquire the land—or the rights to the resources that the land holds—from the local, regional and national governments. In many countries, the land’s potential has great value for large-scale agriculture or mining operations, for the timber in the rainforests that have grown there for hundreds of years, and governments are practically giving away this potential in the name of economic development.

In Laos, conservative estimates acknowledged by the national government place the amount of land in resource transactions at 1.1 million hectares at the end of 2012, more than the total amount of land allocated to growing Laos’s largest agricultural commodity: rice. Unofficial estimates of concession lands, however, reach more than three times this amount.

These transactions help fuel impressive macro-economic figures. The gross domestic product of Laos, for example, has grown by an average of 8 per cent a year over the past few years.

But development can mean different things depending on your perspective. In the agriculture sector, huge profits are generated through industrial plantations labelled as development projects on lands often given away by governments. These benefits are not always shared with those in need, nor do they always take into account the needs of those already living there. In fact, some projects do not have global benefits and some actually create poverty, especially where investment takes place on a large scale and rapid pace, in countries with weak legal frameworks and without the capacity to negotiate and monitor these mega-projects.

Thus, projects fuelled by foreign direct investment should not be blindly embraced around the globe when they involve natural resources that indigenous peoples and local communities already use for their livelihood. The question of economic development should centre on people and how to improve their lives, not take away what they have.

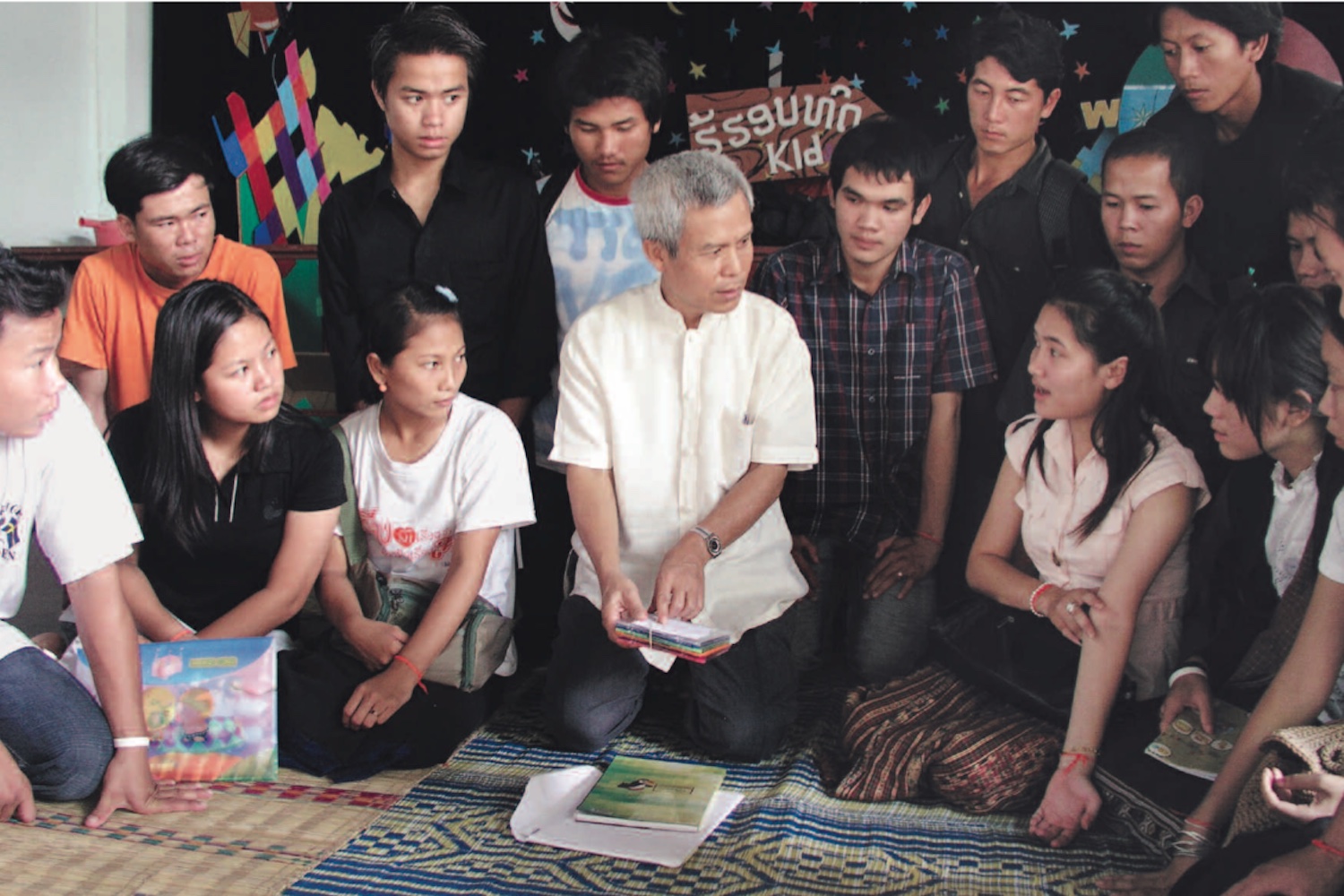

This was the work of Sombath, a prominent civil society figure and community leader in Laos who has been advocating for people-focused development and for protecting the environment on which Laotians depend for their sustenance. He created the first open space where people could share their experiences, and they talked—not about economic growth, but about happiness and suffering.

There is a growing competition for the developing world’s rural forest and dryland areas that globally directly affects the lives and livelihoods of over two billion people. What’s worse, there is an assumption that the land is “empty,” that hundreds of thousands of hectares are devoid of communities because they have not been “developed.”

The notion is absurd. If even the harshest reaches of the Gobi and Sahara deserts support nomadic communities, then how can the lush landscapes of Southeast Asia and elsewhere be expendable, especially where arable land is limited, food security is threatened, and livelihoods are vulnerable?

Under the current system, the imbalance of power and the lack of a speaker for those affected result in top-down, non-participatory and exclusive decision making. This in turn fuels a growing number of land conflicts in too many parts of the globe. For communities losing their land, seeking justice is a highly complicated, hazardous and sometimes dangerous way to go.

As the call for broader and more inclusive debates on development is heard in Laos and elsewhere, those championing the views of the people are under threat and voices of dissent are being silenced. Sombath’s disappearance could just be more tragic evidence of such a trend.

There is an urgent need felt all over the world, in Laos and in many other countries as well, to secure land rights as a driver of true and inclusive economic development, environmental stewardship and food sovereignty. The international community must embrace this need as it rewrites its goals to end global poverty. The challenge will then be to turn words into action, so as to make a difference in the lives of the people development is supposed to help.

A growing number of voices are saying that governments should not favour foreign companies over local farmers, that the land should feed the villages first. As a Lao woman told me, “land is our food, land is our wealth, land is our soul.”

In giving away the land, developing nations of the world are indeed giving away more than their sovereignty. The people of Laos—especially those that Sombath Somphone championed—are the most recent witnesses to the darkest side of this transaction.

Anne-Sophie Gindroz, the former Laos Country Director for HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation, was expelled from Laos the week before Sombath Somphone’s disappearance.

Any views expressed in this article are those of the author and not of Thomson Reuters Foundation.