Radio Free Asia: 30 September 2020

“We note from the addendum to the UPR report that it is the duty of the Lao government to search for missing Lao citizens including Mr. Sombath Somphone, the Laotian spouse of a Singapore citizen. We hope that Laotian authorities will resolve the case expeditiously and bring about the much-needed relief to his family,” said En Yu Keefe Chin.

UN members and NGOs called on Laos this week to resolve the forced disappearance case of a prominent rural development expert and stop censoring and jailing peaceful critics, as the Southeast Asian nation faced a review of its rights record in Geneva.

In a hearing Monday at the United Nations Human Rights Council, Laos was questioned over the 2012 disappearance of Sombath Somphone, its highly restrictive media environment, and freedom of religion – with one NGO crediting Vientiane for some improvements in treating religious minorities.

Singapore’s representative used the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Lao’s rights record to highlight the case Sombath Somphone, whose wife is Singaporean.

“We note from the addendum to the UPR report that it is the duty of the Lao government to search for missing Lao citizens including Mr. Sombath Somphone, the Laotian spouse of a Singapore citizen. We hope that Laotian authorities will resolve the case expeditiously and bring about the much-needed relief to his family,” said En Yu Keefe Chin.

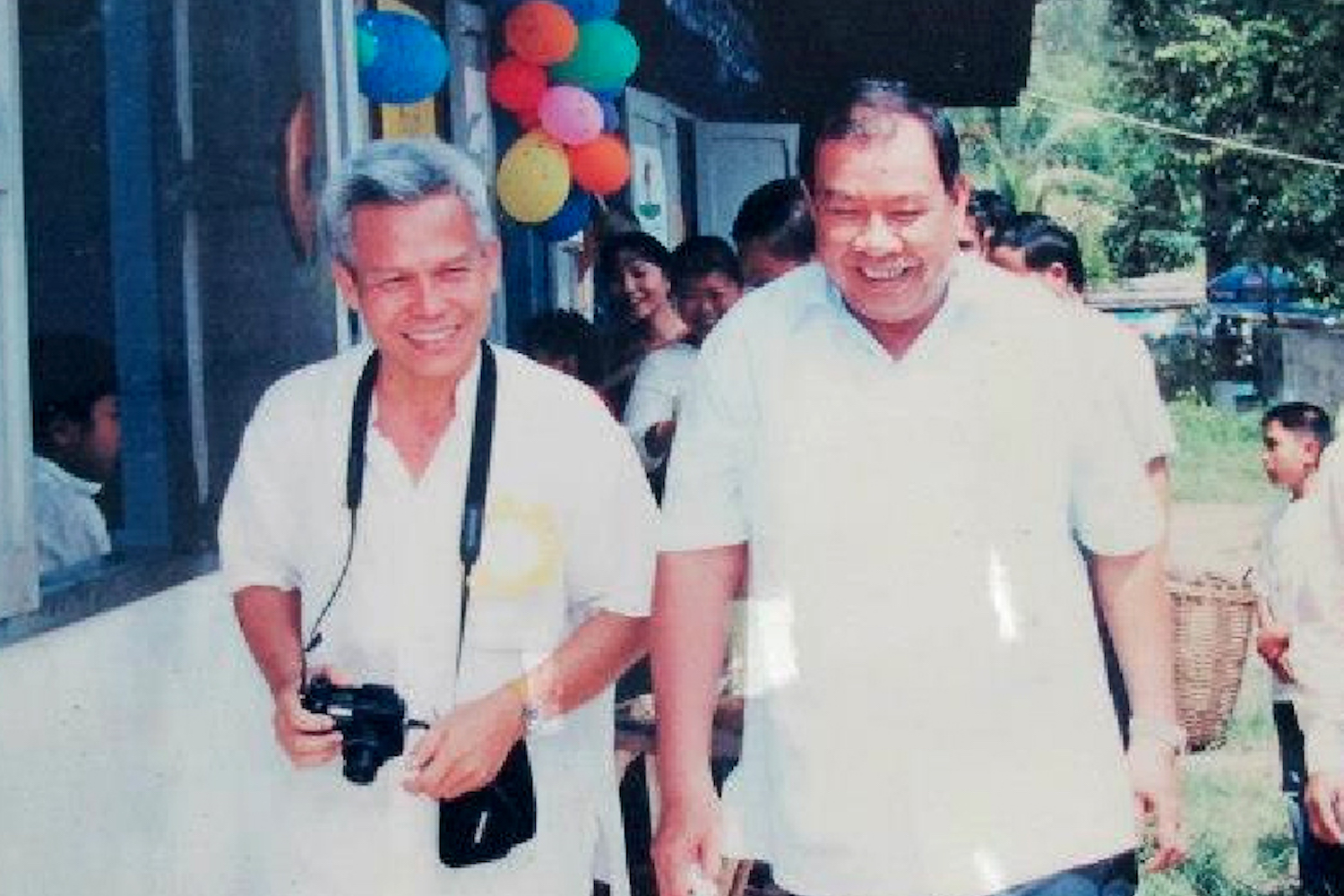

On December 15, 2012, police stopped Sombath Somphone in his vehicle at a checkpoint on the outskirts of the capital Vientiane. He was then transferred to another vehicle, according to a police surveillance video, and has not been heard from since and the government has not offered information.

Before his abduction, Sombath had challenged massive land deals negotiated by the government that had left thousands of rural Lao villagers homeless with little paid in compensation. The deals sparked rare popular protests in Laos, where political assembly and speech are tightly controlled.

Cecilia Andersson of Britain also raised Sombath Somphone, saying

“We regret that Lao PDR did not support the U.K.’s recommendation to undertake impartial and thorough and transparent investigations into all enforced disappearances.”

Freedom of expression and religion

The U.K. however was most critical about Laos’ record on freedom of expression.

In an annual survey of press freedom released in April, Laos was ranked 172 out of 180 countries by Paris-based Reporters Without Borders (RSF), which said the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party “exercises total control over the media.”

Laos also routinely detains and punishes dissenters who air their grievances on social media platforms like Facebook.

“The U.K. notes the Lao PDR statement that the constitution and related laws guarantee freedom of expression, however we remain concerned about restrictions on foreign news agencies and the use of intimidation against critics of the state. We ask the government to promote and protect the right of freedom of expression for all,” said Andersson on Monday.

Meanwhile, London-based Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW) acknowledged that although the country has improved its protection of religious rights, weak rule of law and ambiguous rules and obstacles undermined freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) for religious communities in Laos.

Christians make up about 1.5 percent of Laos’ predominantly Buddhist population of nearly 7 million in three main churches — the Lao Evangelical Church, Seventh-day Adventist Church and Roman Catholic Church.

RFA reported this month that Members of Lao Christian communities were working with central government officials to inform rural authorities of a law protecting the evangelical church in areas where harassment of Christians continues.

“Over the past decade there has been a reduction in the number of long-term Christian prisoners of conscience, however, improvements to FoRB are restricted to urban areas,” said CSW’s United Nations Officer Claire Denman at the council meeting Monday.

“Christians in rural areas have reported incidences of arbitrary detention, forced eviction, confiscation of land and livestock, destruction of property, harassment and discrimination,” she added.

Rejected recommendations

Of the 226 recommendations made by the international community during the UPR process, Laos rejected 66, citing various reasons including that some of the recommendations were made with a faulty understanding of the situation on the ground and that others went against Vientiane’s national cultural values and morals.

Laos’ representative to the UN office in Geneva Kham-Inh Khitchadeth said to the council Monday that Laos could not support recommendations pertaining to forced disappearances because they were not based on fact and evidence.

He also explained Laos’ rejection of recommendations on freedom of speech, expression and information, saying those rights “should be exercised with a “heightened sense of ethics and morality.”

The Lao representative additionally dismissed concerns brought up during the meeting by UN member nations and NGOs, without specifying which he was referring to.

“Despite the overwhelming positive feedback, we also observe that some comments were found to be based on incorrect information and omit understanding of the real situation in the Lao PDR.”

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) Monday criticized Laos’ rejection of the 66 recommendations saying Vientiane’s response was “a step in the wrong direction.

“The Lao government’s non-committal response to international concern over key human rights issues signals that right abuses and repression of civil society may continue with total impunity for years to come,” said FIDH Secretary-General Adilur Rahman Khan in a press release issued jointly with the federation’s member organization for Laos, the Lao Movement for Human Rights (LMHR).

“The international community must step up its pressure on the Lao government and puts human rights front and center of its relations with Vientiane,” he said.

LMHR President Vanida Thephsouvanh accused the Lao government of “sweeping its human rights problems under the rug, pretending no one will notice.”

“The international community should not fall for Vientiane’s tricks and, instead, establish clear benchmarks against which human rights progress, or lack thereof, can be measured,” she said.